Planes, Trains and Toilet Doors is the debut book by Matt Chorley examining key events in Britain’s political history, but with the twist that barely any of it is based in Westminster or Whitehall, but in car parks, village halls, and fields, from tales of duels to betrayals via a tooth extraction earning the poor chap in blistering pain the ultimate political prize.

Before discussing Chorley and this wonderful book, a word about the illustrations, which are by Chorley’s The Times colleague, Morten Morland, a superb cartoonist and satirist. You get the distinct impression that he thoroughly enjoyed this commission, because as a mere stripling of a 44-year-old is too young to have drawn and taken the mickey out of figures such as Heath, Wilson, Thatcher, and Major, let alone giants of political epochs prior to the decade of my birth and you get the distinct feeling that he loved it. The future of political cartoons is very safe in his hands, and my favourite here is his wonderful take on Wilson running down the beach in his shorts and sockless shoes. Incidentally, talking about Wilson, he is the proof that spin and presenting a pretend “human” face to the great British public didn’t begin with one Anthony Blair. Wilson went everywhere in public with a pipe glued to the corner of his mush, pipes being a symbol of a “man of the people” – in reality, as soon as his arse crossed the threshold of the door out of sight of prying eyes and cameras, he lit up his real pleasure, rather expensive cigars, then, as now, very much associated with the evil rich Tories.

Chorley is a comedian, columnist for The Times (having previously been political editor at Mail Online), and the presenter of my favourite radio programme Monday to Friday 10 a.m. to 1 p.m., tagged as “politics, without the boring bits!” The creation of Times Radio just as lockdown was bearing down upon us for the first time was a relief to me. I had grown tired of the relentless “BBC-ness” of Five Live, not interested at all in Radio Four’s “History of Spoons”, as Chorley hilariously put it early on, and have no patience whatsoever with listening to Sid Yobbo & Doris Bonkers shouting down the phone on the likes of LBC. The station is my staple news, culture, and discussion listening (Progzilla Radio being the music one, natch) and Chorley’s show is essential for political creatures such as I, and great for listening to whilst working from home (I would apologise to Jacob Rees-Mogg, but I wasn’t important enough for him to leave a note on my desk bemoaning my absence from the office, so sod him).

So, that’s enough of buttering Mr Chorley up. What about the book? It is split into fifty chapters, each one bringing us the venue where politics was influenced or changed, and the story behind it. It would take too long to discuss these with the detail I enter in my album reviews or interviews, but I do want to concentrate here on two chapters which I especially enjoyed and learned new things from.

My first conference as a (callow young) trade unionist was 1986 in Brighton with the (then) Civil & Public Services Association, a hotbed of “radical” left wing politics fighting against the “right-wing” labour movement establishment. I remember amongst the plethora of leaflet hawkers (“Socialist Worker, Socialist Worker, if you hate the Tories, you’ll LOVE the SOCIALIST WORKER!”) one supporting strikers at a well-known bed manufacturer calling Neil Kinnock (who had not endorsed the strike) the biggest traitor to socialism since Ramsey MacDonald. It was taken as read that to be a “proper socialist”, then you had to decry the descent into establishment collusion by the politician who was still loathed and a byword for sellout all those years later.

The chapter details his home, The Hillocks in Lossiemouth in Christmas 1923, eleven years after the death of his beloved wife, and twelve after his son passed. Chorley’s writing makes it clear that he has an empathy and sympathy with his subject. MacDonald’s ascent to power was remarkable, the illegitimate son of a housemaid & farm labourer, he saw his father once when his mother took him to the top of a hill and pointed out the ploughman in the valley below. You would reasonably think that this would mark him out as a remarkable human, a triumph over the most adverse of circumstances, especially when deference to the ruling classes was almost universal, yet he will forever be marked out as a traitor by his party. His writings are held in a box at The National Archives, seldom asked for. When he successfully won the Labour Party leadership, he was MP for Aberavon, not far from where I live in SW Wales, the seat which includes the massive steel plant in Port Talbot, recently in the news as the old furnaces are being replaced by newer technology at the price of thousands of jobs.

At the 1923 election, Stanley Baldwin’s Conservatives were the largest party, but the biggest loser having shed 86 seats. The press and commentators were full of nonsense of how the end of civilisation was nigh as a bunch of commies and loonies could take charge of the country as the Liberals would not support Baldwin – plus ca change! Chorley goes into some detail as to how he formed the first Socialist government and how this did not “frighten the horses”, including King George V. In other words, making the party acceptable and not a threat to the established order. His government did not last long, and he lost the ensuing election after the Liberals voted them down (again, some things do not change – the Liberal Party is not a particularly trustworthy party or partner). When his party won the most seats in the 1929 election, the term was hit by the Great Depression, and instead of resigning, MacDonald accepted the King’s advice to form a national government of all three parties. For this, he was denounced. Not many years later, when Churchill did the same for WWII, he was booted out by the electorate in the ensuing 1945 election. After Clegg’s formal dalliance with Cameron, the 2015 election saw the Lib Dems rather routed and a majority Conservative administration which, arguably, brought about the greatest social and economic change since the end of the war with Brexit. For all our talk about political parties cooperating in the national interest, when they do, we give them a bloody good hiding. We get the governments we deserve, good people. The story of MacDonald being supported by his daughter to retirement is touching, and you come away from this wonderful chapter rather moved and with a better appreciation of a groundbreaking man.

The second is the fascinating story of how modern political polling came into being just before WWII and was refined in its aftermath. The chapter relates how a chap by the name of Harry Field returned home to Britain having experienced the innovative polling methods developed by George Gallop in search of an academic who could use similar methods. Said academic was Henry Durant. Right from the word go, you could see how devilishly clever this science was. In 1937, Britain’s were asked whether the grounds for divorce should be made easier, this at the time of the national preoccupation and scandal revolving around a King intent on marrying an American divorcee. Genius, really. They started polling at by-elections, and the actual election results were uncannily like those forecast in the polls. Thus, was born an entire industry. These days in The Times, we get a weekly poll which has consistently predicted the political death of the chap with the short trousers and victory for the nasal knight. The story is told concisely of the breakthrough in the 1945 general election in which the polls correctly predicted Atlee caning Churchill (we always were awful ingrates). Chorley does, though, balance this by pointing out the inconsistencies and downright inaccuracies of polls at times. What this chapter, and, indeed, book, does, though, is make one think about how historical episodes and incidents can be directly related to our modern-day politics, and therein lies its longer lasting benefit, as opposed to merely being a good read.

The plotting, the nastiness, the lies, the narcissism, the sheer incompetence. Some things never change, especially our capacity as voters to believe the porkies we are told in the forlorn hope of a better world.

This book is “historical politics without the boring bits” and comes highly recommended. You can see more, and get the book, at https://mattchorley.com/

Writing this review, incidentally, reminds me that I really must put in for that Number 10 quiz of his. Perhaps ten rounds on prog rock?

Dan Jones is a consummate historian. One of a new generation of writers and presenters, I thoroughly enjoyed his history of The Plantagenets and fascinating television series about Britain’s castles and then canals, alongside other works.

Powers and Thrones was published in hardback in 2021, and I purchased the 2022 paperback edition recently. Sub-titled “A New History of the Middle Ages”, it is a superbly ambitious work detailing that period of history from the close of the Roman era in Western Europe to the religious turbulence of the Reformation. That is a lot to pack in, but what I think sets Jones apart is the way he writes and brings his subject alive. Whilst I think it might be somewhat disrespectful to describe it as akin to storytelling, there is a vivid life and colour to his writing which makes this wonderfully accessible alongside being educational.

I like the way he themes each mini period in his chapters. So, we have Romans through to Protestants. More than anything else, though, is the way he puts across what I regard as the most important service a historian can provide to the modern reader, and that is the lessons that we, especially those in positions of power, should learn from the past (and consistently fail to do). Mankind’s constant companions over the millennia, poverty, plague, pestilence, and war, amply described in these pages, continue to haunt, and impact upon us, as do, of course, the egos and narcissism of those in charge.

This review would be too long if I were to delve into each chapter in detail as I do with my album reviews, but there are some highlights in this worth talking briefly about.

The chapter on the Byzantines, which grew insensibly out of the Eastern Roman Empire, contained a lot I was unaware of, with the description of Justinian’s legal code and reforms particularly interesting. The Barbarians take on a new hew, because they were no worse than those they conquered.

Rightly, many of the church leaders come under fire, because (and I say this as a friend of the church) rarely has there been a more cutthroat and despotic group of leaders as medieval pontiffs and senior pastors. The chapter on “Arabs” with the incredible rise of Islam is essential and contains some very interesting and pertinent words on modern day tensions and outright hostility between the differing factions, and the later explanations of the Crusades having a direct bearing on the Middle East’s view on us westerners today, although I was unaware of the fact that the majority of crusades called were, in fact, perpetrated against internal enemies of the church such as alleged heretics and naughty step royalty.

What, though, does shock is the realisation of the vast wealth in the hands of the church and Christendom’s rulers. You think globalisation started with Thatcher, Reagan, Blair et al? Think again, because the merchants and explorers of the middle ages were part of a systemic global market, and the rise of the Italian city states is well described. What does shock, though, is the way the church plundered ordinary souls’ money in the selling of indulgences, that ticket to heaven gained by the hierarchy forgiving all manner of “sins”, in effect both a license to commit sin and to print money by the authorities, a practice which led directly to Luther nailing his theses to the wall. Luther is, incidentally, treated sympathetically here, but Jones does lay bare the nastiness of that era, with the sack of Rome by Charles V particularly fascinating in its use of heretics who had faced annihilation not that long before.

The birth of modern European nations with the rise of the Franks is covered in depth. The culture and the mindset of the knights is given an extended dissection, and of interest is the way warfare changed considerably, bringing the ancient world to a halt. The advances in science and technology were as remarkable in the later medieval period as is the digital revolution we are living through now – epoch and life changing. On a somewhat brighter note, despite some of the despots who took advantage of new world discoveries and evolving weapons, humankind always finds a way to survive. Columbus is given a very revealing pen picture by Jones. You admire him greatly, but had you had the opportunity to meet him, you would likely not be willing to share a pint with him.

For those such as I who needed a better understanding of a period of history often written off as the Dark Ages where little of consequence happened until the likes of Da Vinci and Petrarch bestrode the world, this book is nigh on indispensable.

Sanctuary is a novel by highly regarded young writer, Andrew Hunter Murray, who is a scriptwriter on BBC’s QI. Billed as a sci-fi thriller, there is a little bit more to it than that simplistic label would suggest. It is based in the future, and includes some scientific concepts not available (thankfully, in the main) to us in 2023, but at its heart this novel is a thriller set in a dystopian future written around the age-old themes of wealth inequality, cult leaders & their manipulation of people, borrowing more than a bit from Shakespeare’s The Tempest, loyalty and fealty, both to the leader and to a lover.

As a synopsis, Ben Parr is a young painter whose main subjects are the elderly residents of The Villages, walled communities served by a full complement of essential workers such as chefs, electricians, etc. who reside outside them. He lives in the city (I assume London) with his fiancée, Cara. At the time the novel is set, climate change and economic deprivation have reduced the city to a poverty-stricken husk of its former glory – indeed, this is the case across the UK, excepting where the lucky wealthy can shelter in The Villages.

Cara is a freelance PA, and she left to work for John Pemberley on an island known only as Sanctuary, presumed to be off the coast of West Scotland. Pemberley is a strange and almost anonymous billionaire who was responsible for the setting up of The Villages.

Cara writes to Ben informing him that the island is a paradise on earth, a beacon of light for the future of mankind, a sort of Eden where the impending apocalypse can be averted for a select few.

Parr risks his life to travel to the island using a mix of dilapidated public transport and, thence, a battered boat to cross to the island, almost not making it. When he gets there, and is allowed to stay, Cara is not present, having been posted to a vital job on the mainland.

That is the first main part. After this, Parr meets the main characters on the island. Pemberley is an imposing figure, almost Christ-like to his followers who live and work in multiple disciplines, the very sinister Angela Knight, his right-hand woman, and his daughter, Bianca who befriends Parr and takes him into her confidence. Together, they begin a journey of discovery which leads to the true intentions Pemberley has for his followers and mankind (spoiler alert, they are not altogether welcome). There is a very good tension here as Parr does get sucked into the orbit of Pemberley as he is allowed to paint him and sees him daily, the demagogue confiding in him the way such populists do when they seek to control you.

The final part fair races along, as the true intent is made clear to us, and who or what survives the rush to escape the intent of Pemberley. The close when it comes brings us two revelations, one sort of anticipated, but the other, in the closing lines, not.

I enjoyed this book. Murray does have a knack of pulling you into the world he has created, and unlike other reviewers I have seen, I quite liked Parr as a main character, especially his naivety set alongside his fierce love for Cara and his desire to be with her, come what may.

In terms of the world created The Villages and the ruination of the UK we know in 2023 are wholly believable. Indeed, in many large towns and cities, there are already walled and gated communities guarded by private security separating them from the poor and dispossessed – this novel simply takes that to its natural conclusion.

It is also entirely believable that a person such as Pemberley would splash his untold wealth on what he sees as the solutions to humanity’s problems – we already have that with the likes of Gates, Musk, and Zuckerberg acting outwith normal democratic society. Further, his cult like leadership is also entirely believable with the people working for him falling upon his every utterance as the gospel truth. The bulk of humanity now does this, be it with social media “influencers”, “reality TV stars”, sports heroes, populist politicians & etc. Most people, I am afraid, do not particularly want to live in a world where they are responsible for (and think for) themselves, instead being all too willing to be led. That aspect of the world created is done extremely effectively.

What lets it down, I think, is the ending. I will not spoil this in the review, but I will say that I hope the author is considering a sequel, because there is much left unsaid.

I would recommend The Sanctuary. It is an extremely well-written book, its 387 pages packed with action and clever dialogue.

I usually read factual books, histories, biographies, and the like, as the reviews on this page suggest (and this is an area of the website I want to expand to consider some of the hundreds of books on the shelf).

However, sometimes you simply fancy reading a good yarn whilst ensuring that it is an intelligent one, and that is where I am with my reading now.

Robert Harris is a master storyteller. I thoroughly enjoyed his novel, The Second Sleep, about a medieval world, essentially a theocracy being formed in a post-apocalyptic future. With that, his essential Roman dramas, and this wonderful tale of the chase across The Atlantic of two regicides, he has the knack of introducing unfounded fictional drama into known events seamlessly to believe in the world created utterly as if it were relaying the truth of our world.

This book came in handily, given that I had just finished reading the history of the Suffolk Witchfinders (review below) and last year read an interesting history of Charles I himself. The English Civil War was a period I was not intimately familiar with, so, as ever, a bit of learning is always a positive thing.

What Harris does so well is to immerse the reader in that period and that world. It was, undoubtedly, existentially traumatic for this country. Its roots lie, of course, in the split from Rome by Henry VIII and the trauma of the decades which followed under Tudor & Stuart monarchs, letting a big cat out of the bag by encouraging dissent against absolute power, essentially choosing which absolute monarch suited your view of the world. It reached its apogee with the beheading of a king still regarded by him and his followers as God’s Anointed, with only the Almighty capable of defenestrating him.

Thomas Cromwell became Lord Protector, having solved the argument about who ruled Britain, Parliament, or Monarch – it was the former, but the irony was, as Harris sets out wonderfully, that this vain man effectively became a monarch to replace the man he defeated and raged and dismissed an ineffectual Parliament.

The central characters in the book are Colonel Edward (Ned) Whalley and his son-in-law Colonel William Goffe, two signatories to the warrant which executed Charles I and very close advisers to Cromwell himself. They are real historical figures. Obsessed with catching them and their fellow king-killers, because his wife died in childbirth because of contact with them, is Richard Naylor, essentially a seventeenth-century James Bond figure who is fictional, but with the caveat that Harris believed after research that such a figure almost certainly existed, and I agree.

Harris paints his canvas with chilling ease. The stark description of the fate which met the regicides who were either caught in, or brought back to, England, namely being Hung until unconscious and then taken down from the scaffold, resuscitated, placed on a table, and then Drawn, penis and testicles cut off, with the bowels then removed before the heart was cut out still beating, and Quartered, the corpse cut into four and displayed at various points around the city. There is an incredible, and true, reconstruction of a prisoner awaiting his fate being forced to watch his comrade going through this procedure, with the butcher, hands covered in blood and guts, asking him how he liked his handiwork, cooly responding that he liked it not and to do his worst when attending to him. Incredible bravery in the face of an agonising death, no matter what your views on the crime.

In this vein, you do end up having at the least a sympathy with, and a liking for, Whalley & Goffe. The latter was a devout Puritan, the former racked with guilt and doubt. The description of the New England towns they sought refuge in places you there, and the very knowing discourse these people had with Native Americans. You learn that far from the modern misconceptions of these people they did drink, and they also enjoyed pipes of tobacco. As I pointed out in my review of Witchfinders, they were ultimately doomed as a mass appeal outfit by their insistence that only The Elect were headed for an eternity with The Lord, and everyone else was doomed to a hot outcome. Not exactly guaranteed to find favour amongst the hoi polloi.

Naylor was driven, to the nth degree. This is believable. His wife died tragically, in his mind as the direct result of the men he was chasing. He is, though, fallible, and he is also subject to men more powerful than he, and the bitterness he feels sometimes adds to the reality of the scenario Harris paints. He is a great believer in the institution of the monarchy but recognises the weaknesses and “sins” of Charles II, a chap who would shag anything that moved without the slightest moral regret. Unlike Bond, he makes mistakes, and he lets his quarry slip on more than one occasion.

It is his drive, though, which leads to the denouement, his trip across the ocean (a sixty-three-day vista of H2O stormy hell), his almost seduction of Goffe’s wife, and the end, which is as shocking as it is unexpected.

Act Of Oblivion is a tremendous book, and epic gives it justice. Compulsory reading.

Witchfinders is a chilling historical narrative written by Malcolm Gaskill, a historian and academic at The University of East Anglia, way back in 2005. It arrived in my house courtesy of Jared, my friend on Prog Archives. Last year, the pair of us went along to see Magenta at Acapela near Cardiff, a favourite venue of mine, this hot on the heels of the release of The White Witch – A Symphonic Trilogy. You can see my review of this fine work at https://lazland.org/further-2022-reviews/magenta-the-white-witch-a-symphonic-trilogy Jared subsequently sent me this excellent book.

It is meticulously researched and is an academic work as opposed to a pulp fiction. Perhaps the only slight criticism I can start with is that the names, especially of the wretched victims, and ancillary players in the gaols, assizes, and wider society tend to get a little bit lost and overwhelming. This is, though, a minor whinge, because this book does put across extremely strongly the suffering of the primary victims (the “witches”) and especially the social and religious backdrop in the seventeenth century.

England in the mid-1600’s was wracked by religious tension and ultimately civil war. It was the ascension of The Puritans, strict Protestants, at the heart of this, with their manipulation of ordinary peoples’ loathing of “Popery” and a general fear of God. It has to be said, though, that these devout people didn’t exactly have a long-term commercial message to sell to said people, a reason for their relatively short-lived part in our history. Basically, there were the select Righteous few, a tiny proportion of mankind, who were guaranteed entry to everlasting sight of God (no booze or sex, though, somewhat regrettably for them) and for the remainder, eternal hellfire with no hope of redemption whatsoever. Looking at this with 21st Century eyes, it must be said that this was not exactly an advertising executive’s wet dream and the chaos which directly led to a King’s decapitation followed by the attempt to impose (most unsuccessfully) an end to “Merrie England” was the beginning of the end for a long history of formal religious manipulation of the country’s subjects, and The Age of Reason was just around the corner.

It was, though, a long corner, and one of the biggest tragedies was the narrative of Matthew Hopkins, the “Witchfinder General”, and John Stearne who campaigned across East Anglia in a legal reign of terror, whipping up local populations who readily (indeed, directed by Ministers’ on pain of death) believed in, and were prepared to condemn, witches, Satan’s special helpers who they believed were hellbent upon overturning the rule of Christ and hastening the fervently believed end days – remember, this was a time of not only war, but plague, superstition, deep poverty, and shockingly authoritarian government.

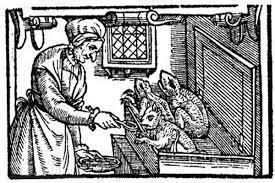

The book brings us the confessions of the witches in great detail, concentrating especially on their imps, creatures who took the guise of domestic and wild animals, but were, in fact, instruments and devotees of Satan, suckling at the witches’ familiars and giving them love and reassurance. The usual end to such confessions was a climb up a ladder on the gallows pole, a noose around the neck, and a drop into oblivion, in many cases helped along by distraught relatives pulling on their feet to lessen the obvious pain and distress of suffocation.

When you start to read these accounts, you wonder at first just how these (overwhelmingly) women could possibly make such outlandish confessions such as the following:

“On the same day, Joan Cooper confessed to the magistrates that she had killed several children at Great Holland. Anne Cade was similarly forthcoming. She admitted to having used a deadly sparrow-like imp called (imaginatively) “Sparrow” to fatally torture Grace Wray, a woman of yeoman stock who had refused to give her tuppence. Bridget Mayers was accused of having cared for a secret mouse-imp called “Prickears”, an offence for which Dorothy Walters had sworn as a witness, perhaps even as a searcher”.

Said searchers would find familiars on the bodies of women. These days, we would call them piles, warts, various skin conditions, but then it was a sentence of death to a suspect, the vehicle by which imps would suckle and provide sexual gratification to the evil women who, if they weren’t plotting to kill good people, thought only of an eternity of orgasmic sex out with the sight of God (the Devil, of course, having a rather large lead in terms of eternal bliss over God).

What on earth were they all thinking? Confession to sparrows, or mice, or cows, cats,dogs, foxes, suckling at teats, the mark of the devil, and assisting countless women to wrought the evil work of the Devil on innocent, God fearing folk. The book makes clear that a lot of this came from a combination of two deadly societal issues (and they were not, of course, confined to England, but were widespread across Europe), these being the shocking condition of plague- and disease-ridden gaols, enough to drive the strongest mind to not merely distraction, but also confession as a means of escape, even if this meant oblivion, this combined with a superstitious populace, utterly inculcated with the existence of witches, their imps, and the need to follow God’s word to the letter, and for those who might scoff at the peasantry’s foolishness and blindly following the authorities and fellow citizens, I give you the modern equivalents – Chinese communist society, North Korean dictatorship, radical Islam, Donald Trump, Boris Johnson, the shocking way our government deliberately used mass media fear to impose ever more ridiculous and unjustifiable Covid lockdown rules whilst shamefully breaking said rules themselves and leaving the most vulnerable people to die from corporate governmental negligence. This is the lesson I take the most from this book – plus ca change!

This being a serious work of history, there is a welcome absence from much of the modern tendency to have “feelings” and relate 1646 actions to 2023 societal “norms”, no “wailing & gnashing of teeth”. Hopkins & Stearne, therefore, are not presented as the very definition of evil. They were products of their time, although what is fascinating is the relatively unknown fact Gaskill makes clear that villages who were blessed with a visit by these fine upstanding fellows had to pay them for the privilege, and in seventeenth century terms, the fees could be ruinous (national taxation was virtually unknown). Frankly, even without the outlandish nature of the accusations and testimonies, a major factor in the demise of the Witchfinder was that the local economies simply couldn’t afford them, especially when once a couple of wretches had been expurgated, a short time later, there would arise yet another scare. Bloody expensive stuff.

Rebellious religious ministers were also victims, those who smelled of popish sympathies, those who refused to deliver sermons conforming to the strict Presbyterian worldview. Nobody was safe, and the events chronicled here resonate to the present day, in films, TV stories, folklore, and, yes, religious suspicion in vast areas of the world – there are still “witches” executed in the modern day.

Godly zeal. Giving too much power to narcissists. These themes are linked, and this wonderful work presents us with a link between shocking events of yesteryear and the way powerful people and institutions still manipulate the body politic – us.

This is a sober history. Imagine, if you will, after six months literally rotting in the hell of Chelmsford prison being brought up before the beak. The day before judgement is passed, you look out of the tiny, cramped room you are housed in with scores of others, and see the carpenter building the gallows, the hangman (who, it is said, will dream of countless bodies being dumped in a pit as a precursor to eternal oblivion) tying the ropes and setting the ladder, and the sounds of merchants selling their wares to tourists who have travelled especially to witness your execution. Sentence is passed, you are led to the gallows. You are allowed to pray. Some do, in a pitiable manner of the condemned asking God for a final pardon, others curse their accusers, some spit, others pass the Devil’s “spell” upon petrified, but morbidly curious, watchers, and you climb up the ladder in order to agonisingly meet……what? The final mystery all of us must face.

Witchfinders is a fascinating narrative of a shameful period in our history, and goes into great detail about the main protagonists, whose restless souls surely still haunt us to this day.

It is still in print and can be purchased from those nice corporate chaps at Amazon & Waterstones, or, alternatively, ask your local independent bookseller to cop hold of a copy for you.

Whilst in Shrewsbury at the end of October, I was waiting to meet my sister and brother-in-law when it started to rain pretty heavily. There is, of course, only one thing to do in such circumstances when the pubs are yet to open, and that is to walk into the nearest bookshop and browse.

This history of Cosa Nostra is an extremely honest one, written in 2003, but updated in 2006 following the arrest of Boss of Bosses, Bernardo “The Tractor” Provenzano, so nicknamed because he “mowed down” his enemies. John Dickie, the very impressive author, is a lecturer in Italian Studies at University College, London, and was made Commendatore dell’ordine della stella solidarieta italiana (Order of the Star of Italian Solidarity) by the Italian government for his work. The history is extremely striking for the fact that it is a non-Italian responsible for it.

The majority of people who have heard of the Sicilian Mafia will, of course, heard most of it from Mario Puzo’s The Godfather, or more recently, The Sopranos run on HBO and syndicated worldwide. Occasional news stories outside of Italy rarely penetrate the British consciousness, and, indeed, very rarely in the mother country itself, one of the main reasons why the mob has been able to survive for so long. The aforementioned tomes are very idealised, and, in fact, romanticised narratives of this organisation – yes, they both hold violence and feature some pretty nasty characters, but they both very much perpetrate the myth that “men of honour” only ever inflict violence upon each other, and then for sometimes “noble” intent and reasons. The organisation is seen as a bit of an underdog fighting corrupt governments and nasty “feds” or carabinieri.

The truth is very different. The Sicilian Mafia (retitled Cosa Nostra or Our Thing) is inherently a state within a state, one that is thoroughly rotten, corrupt, and throughout its existence, violent and ruthless in protecting its interests and assets. The book also makes it clear that it could not possibly have survived without the at times tacit, and at other times ignorant, involvement of the Italian state itself, a state which for much of its history can barely be described as a functioning democracy – incidentally, there is no sense of higher morals from this British & Maltese citizen. The United Kingdom is the dirty money capital of Europe, with London especially acting as a giant laundromat for rotten Russian and Eastern European ill-gotten gains, whilst the murder of Daphne Caruana-Galizia in Malta for her brave exposure of ties between rotten politicians and mobsters is an eternal stain on that island’s world status, and the continued involvement of mob money in online gambling there is shameful.

The book details the evidential clues which demonstrate that there was an organisation in Sicily as early as the mid-1800’s, following the unification of Italy by Garibaldi. Turrisi Colonna’s early studies in 1864, the incredible reports by Ermanno Sangiorgi, Chief of Police in Palermo at the turn of the century, and the missed opportunities by the state to take note properly and act ensured the survival of what by then had become a criminal enterprise so completely embedded in Sicilian society that it made politicians, controlled legitimate and illegitimate commerce, protected corrupt landowners, and, contrary to popular myth, ensured the continued misery of the peasantry underneath them.

The irony is that the only state institution to ever come near to abolishing Cosa Nostra was Mussolini’s fascist state, and this because, of course, he wanted one master, namely himself. The “man with hair on his heart”, Cesare Mori, Prefect of Palermo, and his relentless pursuit of mafiosi. The deep irony, given the links between American mobsters and the home country (detailed in the book, but only where there is an impact upon Sicily and Italy, because the two organisations became quite distinct in their homeland characteristics), was that upon liberation by the allies, the mobsters were all freed as local men of influence and “good men” as they had opposed Il Duce. The imbecility of states.

The turning point in terms of money was the involvement post-war by Cosa Nostra in the highly lucrative heroin refining and distribution trade. At one stage, you could find a refinery every five minutes’ walk in certain parts of the island. This coincided with the rise of the so-called Corleonesi, with Luciano Leggio prominent. It was the Mafia Wars which broke the back of the complicity by the state, in particular the savagery of Toto “Shorty” Riina, who turned the organisation into a centralised corporate entity and brutally murdered all his opponents in a reign of terror, including the shocking and disgraceful assassinations of Judge Falcone and Borsellino. Numerous mafiosi turned informant, pentiti, breaking the code of omerta which governed much of the internal machinations of the organisation, and the state finally began to take the threat seriously.

However, despite the fact that its income and political influence are deeply reduced, make no mistake that the organisation still exists, and there are worrying signs that it is doing what it has always done after times of trouble, namely lay low, regrouped, and, crucially, readapted itself to modern life and circumstances. I mentioned above the involvement in online gambling, and the corruption inherent in the rape of the countryside in illicit development is still very much in the hands of criminals.

A review can only ever do scant justice to a work encompassing over 400 pages. The book is vibrant, it is extremely forceful in its exposure of crimes, criminals, and the methods by which they prospered. It is a lesson above all else in how complicity by the state and the abject kotowing of a population allows this type of crime to continue and is a lesson not merely of the past, but for the now and our future.

If you can get a copy, it is highly recommended.

ALWYN TURNER - ALL IN IT TOGETHER

Very clever and very readable modern social and political history

Alwyn Turner is an English writer of non-fiction with a number of interesting titles to his name, including a couple on British rock music which I must get. All In It Together is the fourth in a series of books on modern British politics and culture spanning the 1970’s to the noughties, and this book specifically covers the early 21st century, so the Blair era to the period just before Teresa May departed 10 Downing Street.

Turner is a very interesting writer, and this book is full of interesting facts and anecdotes, and it might be noted that the title itself is something of a caustic misnomer – it comes from Cameron & Osbourne’s insistence upon winning power, in coalition with Clegg’s Liberal Democrats, in 2010 that the pain of austerity, “necessary” owing to the financial crash which occurred under Gordon Brown’s watch in 2008, would be shared by all citizens of the UK – spoiler alert – it wasn’t.

More than anything else, what this fantastic modern history does is demonstrate just what a profound period of change we have lived through and how the public’s respect for the great institutions of state (except for the monarchy, rightly, and the NHS, unbelievably) have been worn down by the establishment’s many failings. Banks basically getting away with dragging millions into poverty by gambling as credit brokers to the world and his wife, British tabloids hacking the phones of bereaved families mourning murdered children’s death, national & local government more preoccupied with snooping than upholding the law, the police obsessed with “hate crime” as opposed to the real stuff & etc. I have been a public servant since 1983, and I intend writing a book about my experiences in the civil service when I retire, and I will limit myself to saying this – much of the public’s perception and frustrations are wholly warranted – we on the front line share them.

Above all, it is the politicians who get it “in the neck”, most especially Blair who, ahem, did not tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth vis a vis Iraq, Brown, who made Blair’s life virtually impossible as the shouty ambitious neighbour, Gorgeous George Galloway as a cat, and posh boys Cameron & Osbourne. The lesson one takes away from all of this is the fact that at a time when so much more of our lives are placed in the hands of a centralised state, it is a pity that we have had to put up with chancers who promise the earth knowing full well when they do so that they cannot possibly deliver. What Turner would make of the Covid situation can be looked forward to in a future tome. There is, rightly, a very heavy emphasis on the influence of the populist Farage’s influence on British history. Farage never got elected, despite standing numerous times, but he was a canny media operator in an age when media-savvy meant more than policy and decency, and he took advantage of an understandably sceptical and pissed off working & lower middle-class to achieve his vision of Britain leaving the EU. The history of this, and especially recalling the ridiculous Robert Kilroy-Silk, makes for fascinating reading.

But this is not a depressing book. Turner is a thoroughly entertaining writer, and his research is impeccable, so we have tons of quotes ranging from Oasis to football managers to politicians to reality TV stars. Nothing is left untouched, and this is as much, if not more, a social history as a political one. So, we have some amusing stuff about our favourite media, ranging from Gene Hunt in the incomparable Life On Mars to the incomprehensibly popular Lorraine Kelly to the social phenomena of the great British public’s obsession and involvement in reality television, much of which of course, passes us progressive rock nuts by. I might also add that his dissection of the craziness of British left-wing politics and splits is extremely knowing and hilarious, and I speak as one who, until 2010, was an activist in a very left-wing trade union, PCS.

I really enjoyed this book. Much of it is familiar, but there are some surprises as well, and it is pretty much essential as a modern history.

BELLA BATHURST - FIELD WORK

A wonderful book detailing the realities of modern British agriculture.

Field Work is the latest publication by author and journalist Bella Bathurst, who, as her book sets out clearly, lives on a farm in mid-Wales, a rural area entirely similar to the one I reside in West Wales. Even in today’s modernisation dominated society, and the influx near me of thousands of urban workers commuting long distances to work because housing is more affordable here, the landscape and economy is still dominated by agriculture.

This is an important book. Bathurst is not from a farming background, but, like me, she has grown to love and appreciate the rural way of life. More to the point, every time you the reader sits down to eat a meal, that food has to be produced, and the beating heart of that is the rural economy, the farmers and those who service that industry.

Therefore, Bella tells us tales of not only the farmers themselves, but the slaughterman, whose grisly trade is belied by his bright and sunny demeanour. What about the serious reduction in the numbers of agricultural vets? James Herriot wrote bestselling books about his time in Yorkshire, and when I was young, I lapped them up. Now, however, there is far more money to be made from attending to Tiddles the pussycat, or Rover the woof, and not for today’s students the unbearable hardship of placing one’s arm up a sheep’s arse in the dead of night to right a lamb breached. There are the National Farmers Union “succession facilitators” who help their clients wade their way through Byzantine inheritance tax and legacy issues. We see in all its gory detail how an animal is slaughtered and butchered.

And this is at the heart of this wonderful book. We, the consumer, expect everything to be laid on our plate on the cheap, and the environmental, economic, and societal cost of this is shockingly high. As with all other issues, agricultural policy is decided by a bunch of metropolitan “leaders” in Whitehall (or Cardiff Bay in Wales) who speak the same corporate bollocks as all similar senior public servants. These are a group of people with little or no connection to the areas they are meant to protect, and the result is a beleaguered industry very much in hock to the massive corporate supermarkets who dictate the market. Interestingly, none of the corporate farms Bathurst approaches for a contribution agree to talk to her, instead sending corporate media types in their sharp suits and “shades” to parrot the latest party line.

Diversity in agriculture in this corporate world is regarded with deep suspicion, and each year, smaller operations find it harder to make a living. Brexit has brought with it serious doubts as to sustainability and long term policy.

Yet. Yet, there is hope in this. The people Bathurst writes about are the type of people I meet on a daily basis, and they are like all other people, good, bad, indifferent, clever, thick. The usual mix. There is a very bright note at the end. She talks to a bunch of students at one of England’s leading agricultural colleges, Harper Adams, and all there, a wonderfully diverse mix, speak of doing their own thing in their own way, of managing to make a living without the need for subsidies if only they can raise the finance to own their own business and not be tied to greedy corporate landlords and businesses. As ever, it is the youth and new ways of thinking that will save us.

I thoroughly enjoyed reading this. It is a book every person who cares about where their food comes from should read – or perhaps, it is a book that every person who couldn’t give a toss about where it comes from or howe it is paid for, should be forced to read. It is a modern social history which is literature at its finest.

A book which argues, very persuasively, that British society has become infected by bossiness.

I have been (barring a 15-month career break in 1990/91) a civil servant since 1984. That is 38 years, 40 years if you count my short spell in the RAF before this. I am a career public servant. I would, indeed, have gotten less for murder. It may, therefore, surprise some readers of this review (but not those who know me intimately) that, as with Letts, I hate being bossed about by petty bureaucrats and jobsworths. In fact, I have spent much of my adult life ranting about such stuff and nonsense - one of the reasons why I have never been appointed to a senior management position, I suppose.

Quentin Letts is the political sketch writer for The Times, and formerly The Daily Mail. His appointment was, it is fair to say, greeted with a certain degree of scepticism in some corners of the grand old newspaper, but I enjoy his witty and sharp analysis of the strange goings on and procedural hilarities of the “Westminster Bubble”. This book was, therefore, an auto-buy, and it did not disappoint. Letts is an old-fashioned conservative (small c very deliberate) who lives in rural Herefordshire (a place not dissimilar to rural West Wales) and is a believer that government interference in its citizen’s day to day lives should be as small as possible; that, within the boundaries of necessary laws and behaviours, people should be given the freedom to exercise their common sense. As the blurb for the book says “reasonable people have had enough of being bossed about. And when reasonable people stop respecting the law, society has a problem”.

So, you can imagine the fun Letts has when he lets rip against the micro-managing Covid pandemic period. You know, when you could not meet any more than one person outside on a park bench, or when you could meet Mum & Dad (outside in the garden, bloody freezing to death), you couldn’t go inside for a pee in case you “killed granny”. Naturally, therefore, the likes of Matt Hancock and Prof. Neil Ferguson are well and truly in his sights. He has particular fun dealing with “inclusion” and “diversity”, both of which have morphed into curious, but corporately rich, sets of instructions on what not to say and when not to say it.

This is not a political tome. The targets of his ire are as much Johnson or Gove as Starmer and his crew. It is, rather, a bit of a cry for help. It exposes many of the more silly instructions at local level through to the wishes of the BBC for people not to sing Rule Britannia at The Last Night of The Proms in the wake of Black Lives Matter (an invective subsequently withdrawn). There are some extremely interesting, and quite sad, exposures of the bossiness of The Church of England which led to his family not attending church services any longer.

This book is not a flippant one. In fact, it should be required reading for anyone standing at any level of political elections, or being appointed to a “leadership” position in public service. Sometimes, less is more, and when reasonable people enjoy and empathise with a book such as this, we might perhaps have a more serious issue with modern government than we think.

Derek Scally is a journalist working for The Irish Times and is based in Germany. In this insightful and at times deeply disturbing book, he charts the fall of the Catholic Church in the country once described as Rome’s Favourite, such was the devotion and obedience of its citizens to the Catholic cause. Well, no more.

Before going into any great detail, it must be said that the rise of secularism is not exclusive to Eire, nor to the Catholic Church. In fact, in April 2022, when Pope Francis visited Malta, a Times of Malta poll revealed that over 50% of participating readers were not following his visit and he was criticised widely for his pro-migrant stance, with comments absolutely unthinkable a mere decade ago. At the heart of this revealing book is the scandal of abuse of (mainly) children and women by clerics, and it also must be stated that this is not exclusive to Ireland either.

The book concentrates on two papal visits. The first by Pope John Paul II in 1979 (from which the cover photo is taken) and the second by the present pontiff, Pope Francis in 2018. The latter featured a number of apologies for abuse and acts of contrition, but the turnout was markedly down on the previous papal visit, as was the level of blind homage to His Holiness.

The book provides rich and extremely disturbing detail of the level of abuse suffered by the victims, and the shocking level of both state and church attempts to cover up this abuse. Making matters worse is the fact that even after the government made a conscious decision to rectify matters, the state bureaucracy made practical efforts virtually impossible.

Scally interviews widely, with both sides accorded an opportunity to comment, and he is scrupulously fair in his journalism.

This is a story which demands telling, and it is told extremely well. It makes very uncomfortably reading for those who are Catholics and, at its heart, is a story of how humankind always turns absolute power (which the church in Ireland absolutely held) into absolute misery for the populace.

Very highly recommended.

What a…….bloody great player!

James Haskell is one of those rarities - a public schoolboy (note to readers outside the UK, this means fee-paying, not publicly funded) who grew up to play professional rugby and is a name instantly recognisable to much of the general unwashed public, you know those who do not know their rucks from their mauls.

Much of this is, of course, owing to his appearance on the shockingly dreadful reality TV show, I’m a Celebrity……, but this in itself was aided and abetted by an early “scandal” dubbed Porngate and a subsequent media storm over inappropriate remarks and behaviours during a World Cup. For the former, Haskell puts his hands up regarding immature japes, but, very rightly, for the latter defends himself vigorously and lets rip at the Rugby Football Union “suits” who hung him out to dry. Both of these narratives are hugely entertaining and of interest to those of us who have a passion for the game of rugby.

The title itself, and the delightful cover “explaining” it, pretty much sum up an extraordinarily larger than life character. The book is a hoot from start to finish. His personal life narrative is deeply affecting and you rather admire, and recognise, the huge sacrifices made by his parents to enable him to get to where he got, but also know that he is not the only lucky one in his marriage, but it worked the other way around as well. It is very difficult, unless you are a Celtic bigot, to not like the bloke, and talking of such, his loving descriptions of playing against, and with, the best in the world, show us what sport really is, and it is not narrow minded ignorance.

Of interest in the present are his views on Eddie Jones, the much-maligned England coach, who is once again under pressure following a 2022 Six Nations where it is fair to say that France & Ireland were vastly superior and rightly finished above them. Basically, Haskell loves him. It is pretty interesting when he describes Stuart Lancaster as a coach who treated his players like children, but Jones who treats them as adults, and this explains to me in some detail why the media are still struggling to state that Jones has “lost the dressing room”.

With his career at Wasps (and he is very blunt about the old days of inferior facilities) to France, including a hilarious photo shoot which has to be read to be believed, to his days in New Zealand, there is more than enough for even the most casual rugby fan to enjoy.

Very highly recommended.

Fishy Tales (mainly)

Mark Kelly has been the keyboardist in Marillion for a good 40 years now, and this very welcome autobiography charts his life and career in an engaging fashion.

Kelly is a more interesting character than his Marillion persona would have us think. I don’t just mean the drug-taking, which was probably a given for all rock bands of the period, and most growing up listening to them (I think I was one of the very few who simply didn’t bother, preferring ale and nicotine, healthy pursuits which linger to this very day). There are the ex-wives, one of whom let rip in a pretty scathing review on Amazon, the dogged ambition to improve and to make it from pretty humble beginnings, and, above all, his (and it was pretty much him taking on an idea originating with North American fans) innovative idea to get fans to send the band money in advance to fund his band to tour and to record, safe in the knowledge that the costs were covered up front. Without this embryonic concept of what is now a widespread model of crowdfunding, Kelly is clear that Marillion would no longer be a functioning band. Worst, I think that we could have had the unedifying prospect of endless 80’s reunion and nostalgia tours with a certain Mr Derek William Dick, and that would have deprived us of some of the most creative music of the 21st century - no FEAR, no An Hour Before It’s Dark? Unthinkable!

Of course, the band are at the heart of this work. As the blurb stated, the rise, fall, and rise, which described it perfectly. Because it is easy for us fans to forget just how big and damned popular Marillion were at the time of Misplaced Childhood. Just look at the ridiculous number of 36 year old women named Kayleigh! Well over half of the book deals with this initial period, which is understandable on two fronts, namely that it will sell, and also that the second incarnation with Hogarth is very much still functioning and Kelly has had to be somewhat circumspect in his observations (witness the row with h over “crap” lyrics 12 years ago which almost split the band up - this passage is pretty much glossed over). Egos, drugs, misbehaviours, and jolly japes abound, and it is a fun read, even when describing the band’s descent into barely a cult following in the mid-1990’s after the EMI era had finished.

I will say that I left the book with a deeper sympathy for the fate of founding member and drummer Mick Pointer. He was pushed out of the band by Fish, but with the clear support and connivance of the rest of the band just when they were making it. That Ian Mosley is a far better drummer is not in doubt, but I think that Kelly is being unfair when he states that Pointer somehow miraculously improved by the time he had joined Clive Nolan in Arena - his drumming on the debut was not that bad. There are interesting snippets, including the fact that bassist Pete Trewavas has been teetotal since ramming his car into a verge whilst “under the influence”, which I didn’t know, and for any student of the music industry, the dealings with EMI, Castle, and the foundation of Racket Records are required reading.

I love Kelly’s musical work (check out his side project, Marathon), and I admire this book, which I devoured in a couple of days. He is no angel, and he has the grace to admit that himself, but by the close, you sense that he has found happiness and is also extremely proud of his contribution to a remarkable band - this is right. He should be. Music fans should buy this, not merely Marillion fans.

The end of civilisation as we know it?

There is a choice here for the reader and reviewer. Do we have a bittersweet and romantic view of a period now passing into memory, as encapsulated by the traditional long form of domestic cricket, the County Championship, or a rant by a curmudgeonly miserable old git who fails to see the benefit of anything in the modern era?

In fact, the answer lies somewhere in between these two extremes. The author, Michael Henderson, has been writing about cricket as a journalist for a long time. That he can be seen in The Spectator regularly probably tells you as much as you need to know about his attitude to modern yoof culture. Henderson is older than I. He was brought up on a diet of Edrich and Boycott, whereas my early hero was Gooch - indeed, my first county championship game was at Southend Festival with Gooch opening in 1975. The basic premise of this book, which is a mix of travelogue, memories, and sports journalism, is that the year following its completion was the end of cricket in England as we know it, with the introduction of The Hundred, the brand new biff-bash tournament dreamt up by a bunch of corporate tossers with remarkably little knowledge of, or sympathy for, the traditions of cricket. As it happened, the birth of the tournament was delayed by a year to 2021 owing to a certain viral intercession.

Henderson takes us on a tour of his favourite cricket grounds, whilst reminiscing of the greats who graced them over the years, and meeting the characters who (in ever decreasing numbers now) watch their counties at said grounds. Especially enjoyable is the description of England’s finest test ground, Trent Bridge, and Henderson provides us with some decent reviews of real ale hostelries in the vicinity. The travelogue also includes some stirring memories of classic orchestras and concert halls visited over the decades. Not for him the wilful thuggery of a certain Gallagher brother, but the calm oasis of a Schubert recital in Berlin.

The book is at its best when Henderson talks cricket. As a lover of the sport, a former player and coach, I revelled in his characterisations of greats in the county and international games, and his love of this most English of pursuits shines through every such page. And before most people write his loathing of the 20 over and 100 ball forms of the game as failing to keep up with progress, all you have to do is witness the mediocre state of England’s Test Team in 2022 to realise that the marginalisation of the traditional first class game in summer has had real and detrimental consequences. My own view is a little bit more moderate than the author’s in that it is surely not beyond the wit and wisdom of the game’s stewards and executives to strike a decent balance between the varying forms of the game throughout summer and perhaps drop a tournament or two? I do also agree that the constant pounding of music between each and every ball has become a bloody nuisance. I wouldn’t mind so much if they played anything decent.

Many will object to Henderson’s memories of his public school days, but given the absolute dearth of cricket and rugby being played at state schools these days, if these institutions were to disappear, we would die a sporting death in next to no time.

However, you do not have to agree with the author, or even to like him, to take a great deal of pleasure from this highly readable and enjoyable trip down memory lane. I enjoyed this book and therefore recommend it to readers of this review.